Writing Professional Articles: Know Your Audience

Though it does not occur particularly often, there are occasionally books and articles that become much more popular and well-received decades after being published. Moby-Dick, for example, did not become nationally recognized until three decades after Herman Melville’s death [1]. This highlights the fact that the motives and perspectives of an audience changes with time. Indeed, knowing your audience is critical to any form of writing; moreover, it is necessary to understand how audiences find your writing and how to write both timely and timeless work.

The Audience’s Motive

One of the first considerations to make when writing anything is asking yourself why you are writing and why would a reader read what you are writing. When you understand your motivation for writing, and what you want people to learn from what you write, you will have a better idea of how to word and phrase your writing for your audience [2]. Writers should not pander to audiences, as such writing often feels artificial and shallow. It is recommended to focus on your own motivations for the first draft, and then consider your readership during revisions [3].

Figure 1: It is critical to understand who your audience is when writing [4].

While most articles are either informational or persuasive, a topic I have covered in a former article, article readership can be divided between passive and active [5]. Passive readership is looking for something interesting and intriguing, and generally represents the reading population that focuses on headlines and “TL;DR” summaries. Draw these readers in with engaging graphics and images, informative opening paragraphs, and effective organization. Active readers, on the other hand, are looking for the value of the writing. They want to be intellectually engaged, so write material that will cause them to stop and think. An effective combination of valuable insight and making conclusions easily accessible brings in both reader types.

How Your Article is Found

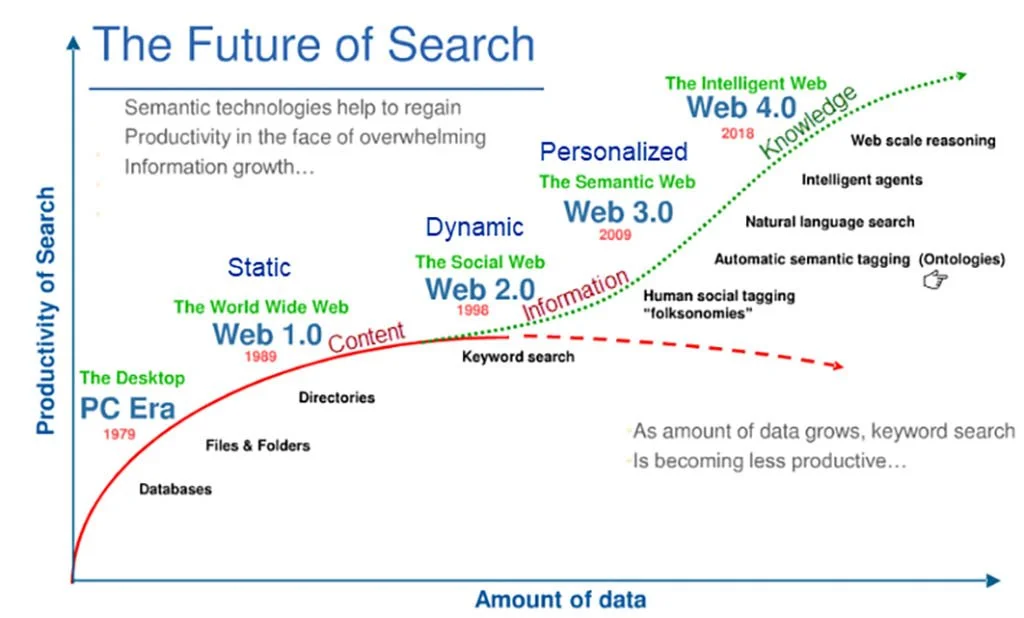

Artificial intelligence (AI) is changing the game for how articles are located online. Whereas browsing the web or using search engines relies on key words, AI searching can determine a user’s intent. A Google search, for example, might be “solar panel cost installation Texas,” whereas a prompt to an AI would be more like, “I have a small 2000 sq ft home in Houston, Texas. How cost effective would it be to install solar panels on my roof?” This latter search in Google (albeit, before AI Overview) would be less effective, but AI can understand the intent behind a real sentence and return more effective answers [6].

Figure 2: Search productivity is increasing because of AI, but it is also causing keyword searching to become less effective. As the amount of data on the Web grows, the value of searching by traditional means decreases [7].

Hence, including important catch words in article titles and search engine optimizing (SEO) your article excerpts that appear on the web are still beneficial, but AI will analyze your text in an instant and determine the value of your article and the reputability of the publishing site (it will also notice your syntax errors, so brush up on that). While not everyone has transitioned to using AI in their web searches [8], the future holds the promise that more meaningful content can be uncovered by AI rather than the first sources to pop up on a search engine taking preference.

Timely and Timeless

As some writing comes and goes, and other writing, like Moby-Dick, only becomes popular later, it is evident that the best writing is a mix of both. Timely and timeless writing resonates with readers now while offering fresh perspectives that can serve as a foundation for future thinking [9]. Generally, writing that is timely and timeless did not become so at the sole action of the author; instead, it was the passion, perspective, and personableness of the writing that enabled its fame and longevity. In short, write about what is most important [10].

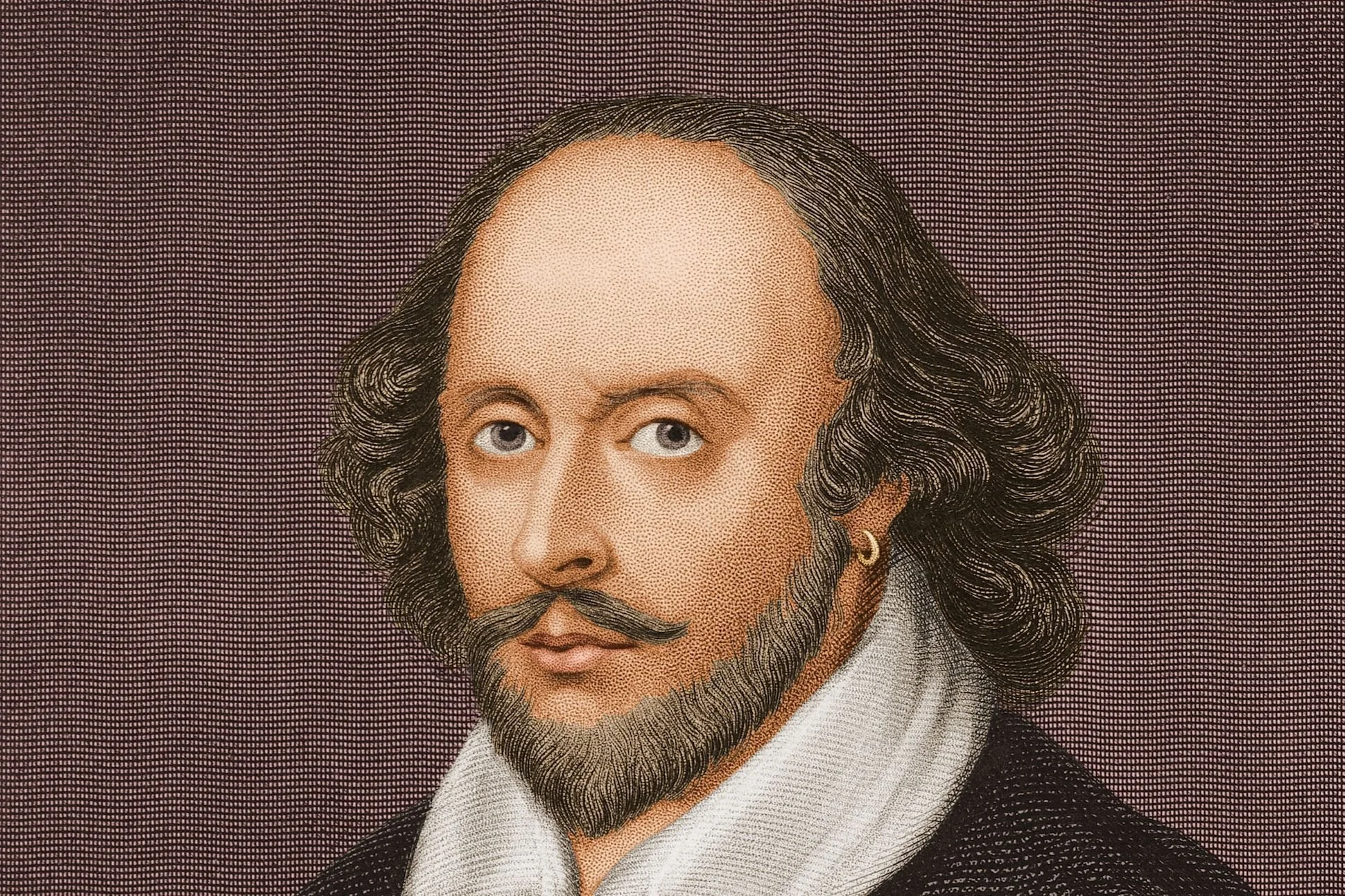

Figure 3: William Shakespeare’s writing was both timely and timeless. His writing was excellent, presented witty and intellectual overviews of society in general, and its general themes relate to even modern readers [11].

Anticipating the reading level of your audience is also particularly important for long-lasting writing. If you are writing on a topic that is niche or academic, use wording that is appropriate and requisite for the topic; on the other hand, writing that is designed to be widely accessible should tend towards verbiage that is more colloquial and less technical. Either way, your writing must necessarily be understandable: prioritize words that enhance precision and clarity.

The next time you write an article, after you write the first draft, take a second to ponder, think, and ask yourself if your article will elicit the response from your readership that you are hoping for, how those readers will find your article in the first place, and if your article contains the sort of substance that will be meaningful and thought-provoking now and decades later.

References

[1] “Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick Published.” EBSCO, www.ebsco.com/research-starters/history/herman-melvilles-moby-dick-published. Accessed 18 Dec. 2025.

[2] “How to Know Your Audience for Better Writing.” Grammarly, 14 Jan. 2021, www.grammarly.com/blog/writing-tips/know-your-audience/. Accessed 18 Dec. 2025.

[3] “Learn to Write for a Target Audience.” Writer's Digest, 21 June 2022, www.writersdigest.com/writing-articles/learn-to-write-for-a-target-audience. Accessed 18 Dec. 2025.

[4] “Writing for Your Audience: What Does It Actually Mean?” Write to Govern, www.writetogovern.com.au/write-audience-mean/. Accessed 18 Dec. 2025.

[5] “Expository, Analytical, and Persuasive Writing.” Purdue Online Writing Lab, Purdue University, owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/academic_writing/rhetorical_situation/purposes.html. Accessed 18 Dec. 2025.

[6] “From Keywords to Conversations: How AI Understands Search Intent.” Absolute Websites, www.absolute-websites.com/blog/seo/from-keywords-to-conversations-how-ai-understands-search-intent/. Accessed 18 Dec. 2025.

[7] “The Impact of AI on Information Discovery: From Information Gathering to Knowledge Application.” The Scholarly Kitchen, 30 Apr. 2024, scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2024/04/30/the-impact-of-ai-on-information-discovery-from-information-gathering-to-knowledge-application/. Accessed 18 Dec. 2025.

[8] “How AI Is Changing Search Behaviors.” Nielsen Norman Group, www.nngroup.com/articles/ai-changing-search-behaviors/. Accessed 18 Dec. 2025.

[9] Friedman, Jane. “Timely vs. Timeless Writing.” Jane Friedman, 3 Oct. 2022, janefriedman.com/timely-yet-timeless/. Accessed 18 Dec. 2025.

[10] “Write About What Is Important, Not About What Is Timely.” The Startup, Medium, 26 Aug. 2020, medium.com/swlh/write-about-what-is-important-not-about-what-is-timely-943a89e498d7. Accessed 18 Dec. 2025.

[11] “William Shakespeare.” Poetry Foundation, www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/william-shakespeare. Accessed 18 Dec. 2025.

To cite this article:

Conover, Dylan. “Writing Professional Articles: Know Your Audience.” The BYU Design Review, 22 December 2025, https://www.designreview.byu.edu/collections/writing-professional-articles-know-your-audience.