Writing Professional Articles: Developing Your Writing

In a world brimming with information, developing your writing is critical to extend the reach of your professional or academic influence and communicate effectively with bosses, peers, and coworkers. As increasing amounts of writing originates from AI, your own writing is also evidence of your own competence and personality. Initially, individuals with a STEM background may not see writing as an integral part of their work, but those who develop their writing abilities will set themselves apart with the capacity to network across the spectrum of academia, industry, and business.

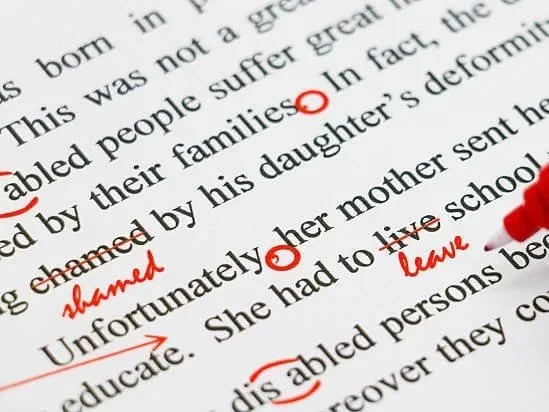

Figure 1: Most writing belongs to one of these four pillars of writing [1].

Determine Your Priority

Generally, your goal as a professional writer fits into one of four categories: narrating an event, describing or reporting on something, explaining and disseminating information, or suggesting a position or approach. In order to determine which category best matches your intended purpose, it is productive to think about how you want readers to react to your material. Usually, the desired reaction is to either have readers change their opinion and mindset or for readers to simply acquire useful information. Narrative and persuasive writing is designed to guide the readers’ thoughts through informed opinions, whereas descriptive and expository writing intend to equip readers with knowledge. Narrative and descriptive writing tend to be more personal while expository and persuasive writing are more logical and direct. Use the following links to BYU Design Review articles to analyze these patterns yourself.

“...think about how you want readers to react to your material.”

Narrative: In technical and professional writing, narrative is personally persuasive writing. Write a narrative if you have firsthand personal experience or expertise. In all technical writing, a foundation of fact and real principles is essential. Experience and expertise supplement citations, because the principles and ideas come from an established, reliable source. Interviews are a subset of narrative writing, and a great example is A Woman, An Immigrant, and A Nuclear Engineer: Interview with Guirong Pan by Emelia Sunday. A more typical narrative article is demonstrated in Getting a Patent the Hard Way by Joe Ellsworth.

Descriptive: This category of writing is personal and informative. Writers can talk about themselves or their own experiences, but the main priority is to highlight a specific product, relevant equipment, or even procedures. This writing is often found in reports and some opinion pieces. Check out The Scarf: A Most Versatile Design by Dr. John Salmon and Good Design: Silly Putty by Grant Ogilvie. An article that is both narrative and descriptive is Quaker Oats and The Design of Everyday Things by Samuel McKinnon.

Expository: This writing is a rich source of information. These articles are designed to answer questions and suggest methodology. All writing takes on characteristics of the author, and there are often opinions in expository writing, but its purpose is to present data and information rather than shape others’ opinions. My article Explained: The Design of Modern Fireworks is information-heavy, but you can still read my opinion when, for example, I explain my perspective on why fireworks are enjoyed in the first paragraph. Another example is Joselyn Corte’s Decomposition in Design. Biographies are almost always expository in nature, such as Hunter Scullin’s America the Beautiful: How Ansel Adams Designed His Landmark Landscapes; they can also be historical and event-based, such as Taylor Heiner’s article Dr. Paul MacCready and The Kremer Prize.

Persuasive: The purpose of writing persuasively is to give your audience information that guides their reasoning to a certain conclusion. Professional writers ‘argue’ their point with much less vehemency than typical arguments; persuasive writing is rarely provocative and more frequently carefully written to make a point. Op-eds, which is a reference to how these sort of opinion articles were ‘opposite the editorial page,’ are the most common example of this type. In persuasive writing, you expect to see claims being made that have to be reinforced throughout the article, such as Adam Roses’s proposition that “Failure is our design mentor” in his article The Doofenshmirtz Design Dilemma: Lessons in Engineering from Danville’s Most Persistent Inventor. Blake Ipsen’s Good Design: Grocery Stores is an article that has both persuasive and expository elements.

Not all writing fits into one of these categories, and there is a vast amount of writing that fits into more than one category. However, if you are able to determine what the overall purpose of your article is, this will enable your writing to be effective at achieving that overall purpose.

Figure 2: This graphic details the order of adjectives. Adjectives closer to the noun are more important, so prioritize those over the less meaningful ones [2].

Finding the Appropriate Style

The guidelines and habits of professional writing will increase the influence of your writing and leave readers impressed and thoughtful. Though professional writing should be formal, it should be positive rather than neutral [3]. Even if you are writing persuasive material, your writing should be concise; though you should write intellectually, avoid vocabulary and jargon that will impede understanding rather than elevate it [4].

A common pitfall for writers is not knowing how to use tasteful adjectives and adverbs [5]. When adjectives are thoughtfully chosen, they add depth and personality to writing. Adverbs are highly descriptive, and most professional writing largely avoids them, focusing instead on precise verbs (unless, for example, I wanted to describe when to use adverbs, and used the word ‘largely’). If you are using a lot of -ly words, refer to a thesaurus and find some new verbs. Consider some examples of good adjective and adverb use and poor use, and note that they are italicized:

Good adjectives: “You won’t always be designing something as glamorous or noble as an MRI machine,” in Natalie White’s article Cushions, Keyboards, and a Customized MRI - Lessons in Human Centered Design.

Poor adjectives: “After Ryan broke up with me, I dragged myself upstairs to my wooden, four-post bed and plush, overstuffed pillows where I sleepily rested my melancholy head, that is until my brother came and got me for evening dinner,” from an article discussing adjectives [6].

Good adjectives: “From clunky desktops to sleek laptops, every generation has seen shifts in form, function, and design,” in Joselyn Cortes’s article Small but Mighty? Mini PCs: A Modern Design Approach to Computers.

Poor adjectives: “The young, male soldier nonchalantly stood with his back against the ornately carved wooden fence and angled his head upwards towards the sky, smoking and staring distractedly at the cotton-ball like white clouds that moved westward above the city,” from another article discussing descriptors [7].

If you go back and reread those sentences, you will notice that the sentences with good adjectives would be grammatically incorrect or less impactful without their adjectives, but reading a sentence without the poor adjectives does not minimize what you learn. Your word choice and grammatical structure will determine how your readers digest what they read.

“Your word choice and grammatical structure will determine how your readers digest what they read.”

Do not by shy about adding in a touch of personal flavor to your writing. This ensures that people will recognize creativity and important ideas, but embracing an irritating excess of iridescent, intriguing, and incompatible words, just to prove a point, is probably not a good idea. Be eloquent, not tongue-twisting. Typically, academic writing should be especially formal, logical, and impersonal when compared to professional writing [8]. At The BYU Design Review, we write in the latter style.

Figure 3: Red annotations are the classic indicator of proofreading [9].

Proofreading and Reviewing

Even with AI, it is useful to proofread your writing. While you might not use a red pen, look back on your initial drafts to see trends in your writing mistakes and catch habits that lead to errors. The more you write formally and professionally, the more natural it will become. As you clean up your writing yourself, you actually become more confident in writing, and your writing experience will flow better and feel more natural for you and your readers. Use AI for a final overview, to catch the things that you did not catch, but realize that if you grow too dependent on AI use, your communication skills will not keep pace with your AI-supplemented writing. Another benefit of developing your writing is that it grows your thinking and communication abilities, because you learn, with time, how to verbalize your thoughts with precision.

“Even with AI, it is useful to proofread your writing.”

There is a difference between proofreading and reviewing. Proofread your drafts first, but then go back and review what you said. Ask yourself if there is substance in what you wrote, which ideas you could expand on, and how you can cut out unnecessary words and sentences. Good writers cut content: most people can only hold on to so many ideas from an article. Repetitively mentioning ideas, using imagery, and writing with patterns are strategies to increase how much readers can retain. Reviewing articles means you give the article a second look. Have others review your articles, too, so that your writing can be subjected to personalized feedback.

Figure 4: A memory schematic. If your readers are filtering a lot of your content, the chances increase that they filter something you did not want them to filter out. The purpose of a conclusion is to jog their short-term memory so your central ideas are stored in their long-term memory [10].

Clarity will keep your readers engaged and more likely to actually integrate the ideas you suggested, adopt the opinions you argued, and think about the information you presented. Contrast that idea with this meaningless paragraph of fluff I wrote, and try to catch what my argument is:

People in the modern day need to know how to write more than just words. It’s an important skill that will help them be successful in their careers. Productive writers know that writing is more than typing words on a computer, it’s about typing words that have meaning for people. The best writers know how to write articles that will be impactful for their readers. You know you are a good writer if people like to read your articles and can appreciate your word choice. You can still be a good writer even if people don’t read what you write or if your words don’t have personal meaning for them. Either way, writing is important, so it’s a skill worth your time and effort to develop and hone.

Instead, I could have written: good writers know how to convey meaning. Using fluff hides your argument and puts your readers’ minds on autopilot, so it should be removed and replaced with sentences that have merit even alone [11]. My own professional writing rarely makes use of emphasis (such as italics or bolded words), but some concepts should be reiterated: sentences worth keeping have value even separated from the rest of your text.

Takeaways

Taking the time to enhance your writing not only unlocks professional opportunities, it also reinforces your thinking and communicating skills. The first principle of good writing is knowing what you want to accomplish and choosing the writing genre that will get you there. When it comes time to put pen to paper or hands to keyboard, use words that augment your thesis, cutting words and sentences that detract from your main ideas. Review your writing to remove fluff and check that the final product stayed true to your original intent.

References

[1] “Types of Essay Writing: What You Need to Know.” Best Academic Writing Tips, Weebly, bestacademicwritingtips.weebly.com/blog/types-of-essay-writing-what-you-need-to-know.

[2] “How to Use Adjectives Correctly: Tips from Grammarly.” Grammarly Blog, Grammarly, www.grammarly.com/blog/parts-of-speech/adjective/.

[3] “General Guidelines for Business Writing.” Purdue Online Writing Lab, Purdue U, owl.purdue.edu/owl/subject_specific_writing/professional_technical_writing/business_writing_for_administrative_and_clerical_staff/general_guidelines.html.

[4] “Style.” The Writing Center, U of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/style/.

[5] “The Case Against Adjectives.” Electric Literature, 12 Mar. 2018, electricliterature.com/the-case-against-adjectives/.

[6] “Editing Tip 1.” NY Book Editors, 13 May 2013, nybookeditors.com/2013/05/editing-tip-1/.

[7] “The Difference Between Academic and Professional Writing: A Helpful Guide.” Penn LPS Online, U of Pennsylvania, lpsonline.sas.upenn.edu/features/difference-between-academic-and-professional-writing-helpful-guide.

[8] “What Is Proofreading?” The Writers Bureau, The Writers Bureau Course, www.writersbureaucourse.com/pages/wb-blog?p=what-is-proofreading.

[9] “Making It Stick: Memorable Strategies to Enhance Learning.” Reading Rockets, WETA, www.readingrockets.org/topics/reading-and-brain/articles/making-it-stick-memorable-strategies-enhance-learning.

[10] “Why You Should Eliminate Fluff in Content Writing.” Elite Editing, eliteediting.com/resources/editing/why-eliminate-fluff-in-content-writing/.

To cite this article:

Conover, Dylan. “Writing Professional Articles: Developing Your Writing.” The BYU Design Review, 8 September 2025, https://www.designreview.byu.edu/collections/writing-professional-articles-developing-your-writing.