Exploring “The Design of Everyday Things”

The holidays are a great time for us to rest, relax, and reflect. So in between semesters at college, I decided to sit down and enjoy a new book. The bright yellow-and-red cover of The Design of Everyday Things immediately drew my attention [2].

Figure 1. The Design of Everyday Things, by Don Norman [1].

I had never really engaged with a design book in the past, so I was not quite sure what to expect. All I had was the basic impression that I would learn more about design for simple, useful products. I soon learned that this book had much more to offer.

Human-Centered Design

The overarching theme that seeps through the pages of this book is that the designs of products intended for humans to use should be human-centered. That sounds obvious, but I was surprised at how much I did not realize. Do you want to design a product that someone can effectively use? Then you must understand how a human will think, how they will act, and how they will use it.

Figure 2. Designs of products intended for humans should be human-centered [3].

One simple example is anything that has a flat top to it. This naturally allows objects to be placed on top of it. Many people, myself included, utilize this feature on top of their refrigerators for additional food storage. Is this an intended feature? I have never seen a refrigerator company advertise how much someone could place on top of their product. And yet, it is a natural tendency for humans to do.

This is fine for a refrigerator, but what if this occurs on a different machine, one where the clutter could be confusing and even cause damage? Taking this into consideration, a designer may adjust the physical layout of the machine to reduce this possibility for error, or add a label to warn others against misuse. This is human-centered design.

Engineers tend to be logical creatures, and focus on how their designs could work when used with precision. People, however, are generally not precise. Norman’s radical idea is that if an imperfect person has difficulty with a product, it is more often than not the fault of the designer in not understanding how a human can or would use it. The designer’s job is to guide the person in using the product comfortably through the implementation of intrinsic design principles.

Seven Principles of Design

There are seven main design principles established at the beginning of the book and built upon throughout. The first is called discoverability, and is defined as the ability of a design to communicate “what [the product] does, how it works, and what operations are possible” [4]. The remaining six principles help to improve this discoverability. They are known as affordances, signifiers, constraints, mappings, feedback, and conceptual models. I will not go into depth describing each of these here, but when considered properly, each one allows us to discover possible and appropriate uses of the product.

I felt encouraged to think about these principles the entire time I was reading. After making it through a chapter or section, I would analyze the everyday things around me to see how well they were designed. I would imagine how people would try to use such a design. It was a fun exercise!

One evening after finishing some reading, I found myself examining a plastic container that held my cereal. Questions immediately arose: What did the container’s design afford me? What signifiers were apparent? What is our conceptual model of cereal containers? How could this be improved? And on, and on. I found that I could now explain why the cereal container was so easy to use, and I had some ideas for how it could be better. Since I am already familiar with these everyday things, the book was incredibly engaging to me.

The Age of Technology

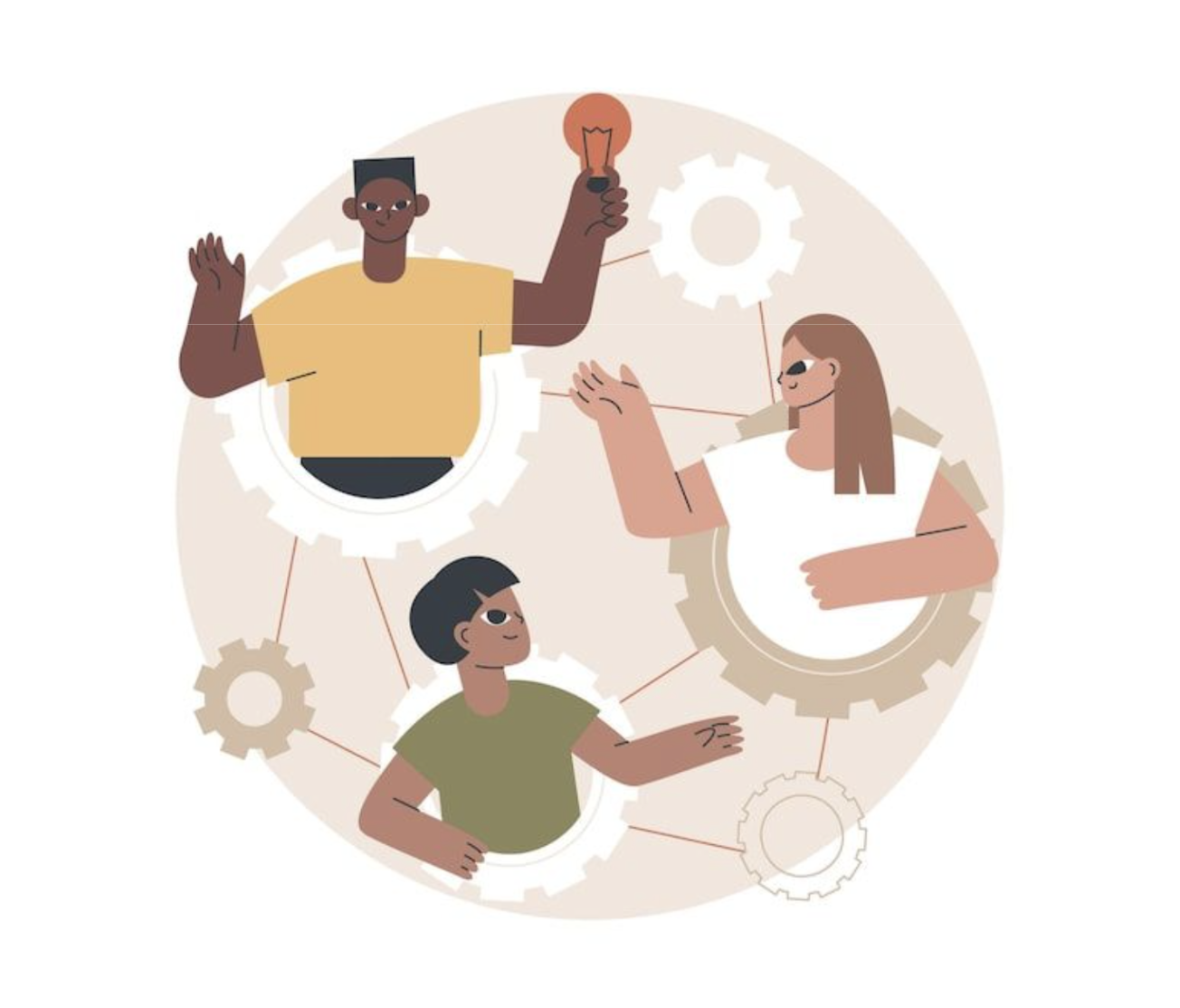

This book was published in 2013, being a revised and extended version. I am grateful for the author’s wisdom in updating many of his examples contained in earlier publications, especially those pertaining to ever-changing technology. I could see how Norman's comments on technology still held up well, even after 12 years, as well as places where a natural gulf was evident between the year this book was published and the progress that has been made since.

One section in particular that caught my attention was “Memory in Multiple Heads, Multiple Devices” in chapter three. Norman touches on the concept of “cybermind,” or the idea of utilizing technology to increase our memory and store information. This made me consider the recent advent of commercial AI models, along with the arguments for and against using them in various settings.

Norman’s ideas from over a decade ago are rather insightful on this matter. In reference to technology, he commented that “Technology does not make us smarter. People do not make technology smart. It is the combination of the two… that is smart.” He also lamented that the more we become reliant upon these external devices, the more we begin to flounder and fail when we are without them [5].

The book does feel dated when discussing a design flaw of older USB ports, pointing out how they are constrained such that devices must be inserted in the correct orientation. This was resolved with USB-C connections, which I was surprised to learn were introduced in 2014 (a year after this book was published) [6]. I have no doubt the author was relieved once this universally irritating design was improved upon.

Figures 3 and 4. Older USB devices must be oriented properly to be plugged in. This is irrelevant in the newer USB-C design [7] [8].

Additional Comments

Norman spends a large amount of each chapter teaching about psychology and human cognition (The first edition of this book was called The Psychology of Everyday Things), then demonstrating how these principles help us understand human-centered design for products. There were places where I got a bit lost with all of the psychology lessons he had to offer.

One such place was the third chapter, “Knowledge In The Head and In The World.” It was difficult for me to picture the differences between the two and why both are so important. Most of these confusing sections were cleared up for me as the chapters progressed, and I could eventually see their significance in relation to design. Some, however, I might need to re-read in order to understand why they were included.

With that being said, I admire Norman’s ability to provide examples of all shapes and sizes to support his points: personal, historical, hypothetical, and even live examples. Since a large amount of this book deals with cognition, at times the reader is asked to demonstrate a cognitive feat to help prove the author’s point. These consist largely of memory exercises and play on the recollection of relevant experiences in the reader’s life. At one point, for instance, readers are asked to try to remember where the doorknob was on the house they lived in three houses ago in order to prove a point.

One of my favorite aspects of this book is how relatable Norman is with his audience. Albeit a technical book, his tone was quite humorous. For example, while expressing frustration at the confusion behind mirrored controls for a shower head, Norman remarked, “Whoever invented that mirror-image nonsense should be forced to take a shower” [9].

Conclusion

The Design of Everyday Things by Don Norman was an excellent read. It taught me that anyone can apply human-centered design principles to create a more usable, innovative product. Now, in order to evaluate some of the designs I have in mind for future creations, I challenge them with the seven design principles detailed by Norman. All-in-all, I would recommend this book to anyone who wants to be better at recognizing good design and contributing to the world around them.

References

[1] The Design of Everyday Things: Revised and Expanded Edition. Gregory, gregory.ph/products/the-design-of-everyday-things-revised-and-expanded-edition. Accessed 14 Jan. 2026.

[2] Norman, Don. The Design of Everyday Things: Revised and Expanded Edition. Basic Books, 2013.

[3] "Human-Centered Images." Freepik, www.freepik.com/free-photos-vectors/human-centered#uuid=eaa5baef-c9d9-49ae-85c5-78f15b64c6a0. Accessed 14 Jan. 2026.

[4] Norman, Don. "Fundamental Principles of Interaction." The Design of Everyday Things: Revised and Expanded Edition, Basic Books, 2013.

[5] Norman, Don. "Memory in Multiple Heads, Multiple Devices." The Design of Everyday Things: Revised and Expanded Edition, Basic Books, 2013.

[6] "USB-C." Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 7 Jan. 2026, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USB-C.

[7] "USB-A vs. USB-B vs. USB-C: What Are the Differences?" Cabletime, cabletimetech.com/blogs/knowledge/usb-a-vs-usb-b-vs-usb-c-what-are-the-differences. Accessed 14 Jan. 2026.

[8] "USB-C Stock Photos and Images." iStock, www.istockphoto.com/photos/usb-c. Accessed 14 Jan. 2026.

[9] Norman, Don. "The Faucet: A Case History of Design." The Design of Everyday Things: Revised and Expanded Edition, Basic Books, 2013.

To cite this article:

White, Dalton. “Exploring ‘The Design of Everyday Things’.” The BYU Design Review, 14 January 2026, https://www.designreview.byu.edu/collections/exploring-the-design-of-everyday-things.