The Return of the Atom

From the microprocessor in the 70’s to MS-DOS and Windows in the 80’s to the World Wide Web in the 90’s to mobile platforms and social media in the 2000’s to Deep Learning in the 2010’s and now to generative AI in the 2020’s, the progress of the World of Bits is almost beyond the imagination of 1976 science fiction. Outside this world, however, there is the world governed by atoms, and progress here has been stagnant now for several decades.

The ubiquitous smartphone touchscreen “slab” was designed almost two decades ago and is the same today, though it doesn’t fit as nicely in one’s pocket.

Look around the airline cabin on any flight and everyone will be staring down at that slab. The flight experience itself, however, has not changed much. For example, a flight from New York to Perth takes 20+ hours today, roughly the same “in-air” time as in 1976, though with only one stop versus three due to fuel efficiency gains. Unfortunately, what we gained in the flight experience from increases in fuel efficiency has been lost at TSA check-in.

Housing in 1976 was built from 2x4s, drywall, 14/2 copper romex wiring, and asphalt shingles. And though we now have double-paned glass as standard, one could argue the overall 2026 house quality has diminished.

It has been almost 90 years since the household washing machine and dryer began cleaning our shirts, but ironing those shirts is still done by hand.

And getting from your house to the grocery store, much to the lament of 1976 futurists, is still accomplished by four rubber tires and an asphalt road. In response to the stagnant world of atoms, Peter Thiel famously said, "We wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters."

After the significant gains in atom-altering innovation that punctuated the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it turns out that achieving another step change in innovation in the domain of atoms was incredibly difficult and required an ultra-complex synthesis of just about every engineering discipline. Halfway through 2020s, however, there are strong signs that our current decade will buck the trend of physical world innovation stagnation and may be known as the decade of the return of the atom. New and current engineers will need to understand this sea change if they are to meaningfully participate in what lies ahead.

Let’s look at three recent atom-centric innovations that are on the cusp of impacting life in the real word in a way that would make Isaac Asimov proud of human ingenuity and progress: ASML’s TWINSCAN EUV machine, Boston Dynamics’ Atlas robot, and SpaceX’s Starship. These three innovations will also give us insight into what lies ahead.

Figure 1: The ASML TWINSCAN EUV machine [1].

ASML - TWINSCAN

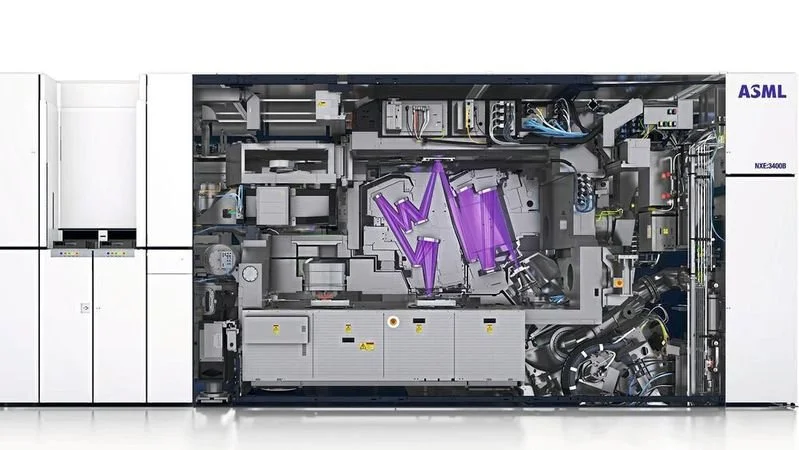

The TWINSCAN performs photolithography in the manufacturing process of the world’s most transistor-dense chips. It generates extreme ultraviolet light by shooting 30 𝜇m droplets of liquid tin in a single-file line at 50,000 droplets per second. As they fly past a target zone, a laser precisely targets and hits each droplet three times, turning the liquid tin droplet first into a pancake-shaped disk and then into plasma which ejects extremely short wavelength ultraviolet light (EUV). The light is used in the photolithography process of a silicon wafer layer. Up to 70 layers of EUV-exposed silicon must be aligned with its previous layers as well as with the photolithography mask to within about 1 nm.

Figure 2: A graphic that illustrates the ASML chip manufacturing process [2].

All this involves ultra-precise and very fast mechanical positioning and repositioning so that throughput reaches about 170 processed wafer layers per hour, which equates to about 2,000 Apple M5 laptop chips. To achieve this throughput, the silicon experiences about 5 g’s of acceleration as it starts and stops during the EUV exposure sequence. And all this is done to about 1 nm accuracy. ASML’s TWINSCAN NXE:3400C is the machine that accomplishes this. Considering the number of parts, subsystem hierarchy and interactions, precision, and the number of physics domains that encompass TWINSCAN, it is the most complicated machine ever built, surpassing even the Large Hadron Collider.

ASML’s TWINSCAN is a masterpiece of engineering, but it is also enabling the design and manufacture of the low-power and transistor-dense computer chips that fuel self-driving vehicles, humanoid robots, and actual flying cars. For example, ASML lithography machines are used to manufacture the most advanced chips, including NVIDIA’s Jetson Thor chip, which is the brain for Boston Dynamics latest industrial humanoid robot, Atlas.

Figure 3: A closeup of the Atlas robot [3].

Boston Dynamics - Atlas

Atlas was unveiled at CES 2026, has 56 degrees of freedom and can handle 70 lb sustained loads for about four hours, at which point it can change its own battery in a couple minutes. It has tactile fingers, 360 degree vision, and torque sensing. Its actuators are custom designed for 360 degree continuous motion that results in its uncanny ability to spin its torso one way and its head in another. Because of the massive amount of on-board computational power (thanks to ASML), it has hybrid offline/online capabilities. Mobility, real-time perception, trajectory execution, and part handling can all run offline on its “Large Behavior Models”, or LBMs. LBMs are similar to LLMs like ChatGPT or Grok, but they are trained on powerful GPU clusters with physical behavioral data rather than text. Once trained, they then run in “inference” mode locally on Atlas. Atlas’ online capabilities enable coordination and collaboration between robots and skill sharing. Skill sharing is especially interesting in that as one Atlas robot learns how to do a task, this skill can be instantly deployed to other/all Atlas robots. Hyundai is the primary shareholder of Boston Dynamics and is planning mass production of Atlas in 2028 to the tune of 30,000 robots annually [4]. These robots will initially be used in Hyundai factories to perform “high-risk”, physically taxing work, but have the potential to accomplish complicated, high dexterity tasks.

Several dozen companies worldwide are in advanced stages of actively pursuing commercialization of humanoid robots and many have recently announced deployments. The “I, Robot” world imagined by Asimov is no longer in embryo but has been finally birthed in the 2020’s. The same factors that led to the realization of Atlas are gestating many other species of automaton, such as driverless ride-hailing services, which entered pioneer markets in 2020 and are now in five cities in the USA and another five in China [5]. There is consensus that the success of the “robotaxi” paradigm is now just a matter of executing proven engineering and overcoming regulatory hurdles; the job of taxi driving will become niche, specialized, and largely extinct. Humanoids and robotaxis are just two low-hanging fruits in the world of automata, and the complexity of the realizable design space in this arena is immense.

ASML’s TWINSCAN machine, a mechanical engineering marvel itself, enabled Atlas. The mass manufacture of Atlas robots will create positive feedback loops in which Hyundai will use its robots to manufacture more of its robots. This positive feedback mechanism is understood by more than just Hyundai, and judging by company roadmaps, no one understands it better than Elon Musk. Tesla recently announced the “Honorable Discharge” of the low-volume Tesla models S and X. The factories that produced these vehicles will not be shuttered but will be converted to the manufacture of (you guessed it) the Optimus humanoid robot.

Figure 4: The Tesla Optimus Gen 2 robot [6].

Optimus will undoubtedly be first deployed to all of Musk’s manufacturing enterprises, including SpaceX. This brings us to our third example, the SpaceX Starship, which if successful, will firmly endow the 2020’s as the decade of the resurgence of the atom.

Figure 5: SpaceX’s Starship is pictured launching from Starbase, Texas, for its 11th test flight on 12 October 2025 [7].

SpaceX - Starship

New space launch systems have generally been synonymous with NASA. Then came the decade of the atom, and in 2025, NASA’s new administrator, Jared Isaacman, shifted priorities from launch systems to launch payloads. The shift was several years overdue as commercial reusable systems are far more cost effective than NASA’s legacy systems. For example, the Space Shuttle cost per kilogram of payload was about $80k in 2026 dollars, whereas SpaceX list price per kilogram is currently around $3k, a 27-fold reduction in cost. This cost is expected to further fall to between $10 and $100 (another ~15-fold reduction) when Starship’s full reusability goals are achieved. The consequences of this massive reduction in the cost of putting things into orbit and deep space will be profound. For example, this could bring the cost of a round-trip flight from New York to Perth to around $15,000, but with in-air travel time of less than one hour. Total travel time will be closer to five hours to account for getting to and from the launch sites, which will need to be more remote than commercial airports. Even so, this is competitive cost-wise with present-day business and first-class airline tickets but at a fraction of the time that passengers spend in the dreaded airline seat. Certainly, this could be the leap in air travel progress that would impress even Peter Thiel and that has eluded us for so many decades. Those costs will continue to fall as all aspects of the Starship supply chain are impacted by autonomous manufacturing due to Atlas, Optimus, and other autonomous robots.

Starship will not be used for international travel this decade, but it will be used to bring commercial tonnage to orbit before the decade is over. The Starship system is the backbone of lunar and Martian bases and putting flesh on that backbone now appears to be “just” engineering. This is certainly a step-change in space technology after decades of stagnation or, at best, incremental improvement.

The TWINSCAN EUV machine, Atlas, and Starship are just three examples of this decade’s step change in engineering with the atom that will likely result in massive transformation, perhaps even upheaval, of the human experience, likely exceeding the upheavals caused by technological advance of the late 19th century. There are many more examples from our decade. For engineers, this is a time of opportunity. ASML has enabled near-general artificial intelligence which spawned the humanoid. AI is also the biggest productivity multiplier that engineering has seen. During the past 50 years, engineering advancement was largely confined by the boundaries of a silicon wafer. The boundary for significant engineering during the next 50 years may have just been expanded to include not just the universe of bits on silicon, but the universe of atoms, which is a colossal universe indeed.

References

[1] "SK Hynix Installs as First Memory Manufacturer ASML’s High-NA EUV Scanner." All About Industries, 2024, www.all-about-industries.com/sk-hynix-installs-as-first-memory-manufacturer-asmls-high-na-euv-scanner-a-ea7f580853b8de5f46856e2e9b19e848/.

[2] "Investment Insights: ASML." Middleton Enterprises, middletonenterprises.com/investment-insights-asml-2/.

[3] "An Electric New Era for Atlas." Boston Dynamics, 17 Apr. 2024, bostondynamics.com/blog/electric-new-era-for-atlas/.

[4] "Boston Dynamics Unveils New Atlas Robot to Revolutionize Industry." Boston Dynamics, 2024, bostondynamics.com/blog/boston-dynamics-unveils-new-atlas-robot-to-revolutionize-industry/.

[5] "Waymo’s Fully Autonomous Rides are Coming to Miami, Orlando, Dallas, Houston, and San Antonio." Fast Company, 2024, www.fastcompany.com/91443871/waymo-fully-autonomous-miami-orlando-dallas-houston-san-antonio.

[6] Edwards, Benj. "Tesla’s Latest Humanoid Robot, Optimus Gen 2, Can Handle Eggs Without Cracking Them." Ars Technica, 13 Dec. 2023, arstechnica.com/information-technology/2023/12/teslas-latest-humanoid-robot-optimus-gen-2-can-handle-eggs-without-cracking-them/.

[7] Lea, Robert. "Getting Even Bigger: What’s Next for SpaceX’s Starship After Flight 11 Success?" Space.com, 2025, www.space.com/space-exploration/launches-spacecraft/getting-even-bigger-whats-next-for-spacexs-starship-after-flight-11-success.

To cite this article:

Terry, Benjamin. “The Return of the Atom.” The BYU Design Review, 18 February 2026, https://www.designreview.byu.edu/collections/the-return-of-the-atom.