How Dating Apps Are Designed

Over 350 million people worldwide use dating apps [1]. Considering this statistic, you probably know someone who uses them. Maybe you know someone who met their spouse through one. I know I do. The dating app industry generated over $6.18 billion in revenue over the course of 2024 [1], so it’s no surprise ads for apps like Tinder and Bumble appear almost everywhere. The dating app Mutual, which is Utah-based, often funds campus social activities, and its banners can be seen covering a football stadium. Dating apps seem impossible to escape, especially when it seems everyone is participating in the online dating scene. What’s the appeal, how are they designed, and why have they become so embedded in our digital landscape?

Tinder’s co-founder, Jonathan Badeen, came up with the idea for swiping while wiping fog from a steamed mirror, describing it as the “easiest and most natural way for users to navigate from one potential match to another” [2]. The motivation behind Tinder was to treat each profile as a card where you can swipe through the ‘card stack’ to find what you want. The founders, Sean Rad and Justin Mateen, talked openly of wanting Tinder to feel gamified where the user would want to swipe even if they weren’t looking for a date [3]. This design reframes dating as fun, exciting, and dependent on chance. The stakes, however, are not points or levels, but love, sex, and validation.

Sociologist Zygmunt Bauman argued that modern technological change had transformed long-term relationships into low-commitment connections. In what he calls liquid love, relationships are easy to enter and easy to exit, with minimal emotional investment [4]. Dating apps embody this logic through their design. When users are rewarded for continued app engagement rather than relational success, commitment becomes less attractive than staying in the game.

Because of higher rewards being associated with swiping, matching, and validation, there is less of an incentive to invest in just one person. Users are encouraged to maximize their utility by remaining noncommittal. The choice then needs to be decided between an instant gratification of multiple partners and validation or the vulnerability and risk that come with committing to a single relationship.

Bauman introduces this same form of disposability, noting users can be “secure in the knowledge they can always return to the marketplace for another bout of shopping” [4]. The more options available, the greater ability to go back and find something ‘better.’

In theory, this makes dating apps a game where the stakes are love and sex. It also introduces to the user a plethora of options, potentially exposing the user to more options than they can choose from.

I think about it this way: in 2013, a TV show named Brain Games released an episode titled “You Decide,” which explored the paradox of choice. Put simply, the paradox of choice reveals that the more options available, the harder it is to choose due to having more choices to weigh [5]. This can be related to dating apps. The more people you have to choose from, the harder it is to decide. When faced with an endless stream of potential partners, users may struggle to commit, instead engaging in a never-ending search for something better.

Clinical psychologist Dr. Alina Liu explains that “with the perception of ‘choice in abundance’, it can become harder to know when to stop searching.” She compares dating apps to shopping in a massive grocery store rather than a small corner store: “Because of the endless possibilities, we are pressured by the illusion to find the ‘perfect’ partner” [2]. This illusion can make satisfaction feel constantly out of reach.

Figure 1: This chart displays the amount of users who participate in multiple dating apps at once. 36% of dating app users install more than one which increases their pool of potential partners [6].

The appeal of dating apps lies in how effectively they use reward-based psychology. According to the Atlantic Journal of Communication, dating apps offer an instant gratification model whereas dating websites are designed for more substantial and longtime use. Dating becomes more of a novelty and excites your emotions to make the whole experience more enjoyable [7].

Furthermore, the act of swiping, as seen on dating apps like Tinder and Badoo, "transforms the act of swiping into a highly rewarded activity similar to slot machines” [8]. Winning equals a match, offers the promise of connection, and reinforces the urge to keep swiping. Over time, the behavior becomes habitual, even addictive.

In traditional dating, meeting someone typically happens through shared physical spaces. These environments provide built-in context: shared interests, social accountability, and gradual relationship development. Interactions unfold over time, with fewer simultaneous options. Dating apps, by contrast, remove many of these constraints. They collapse geography, social networks, and context into a single interface, allowing users to meet hundreds or thousands of potential partners with minimal effort and social cost. This shift fundamentally changes how people encounter and evaluate potential partners.

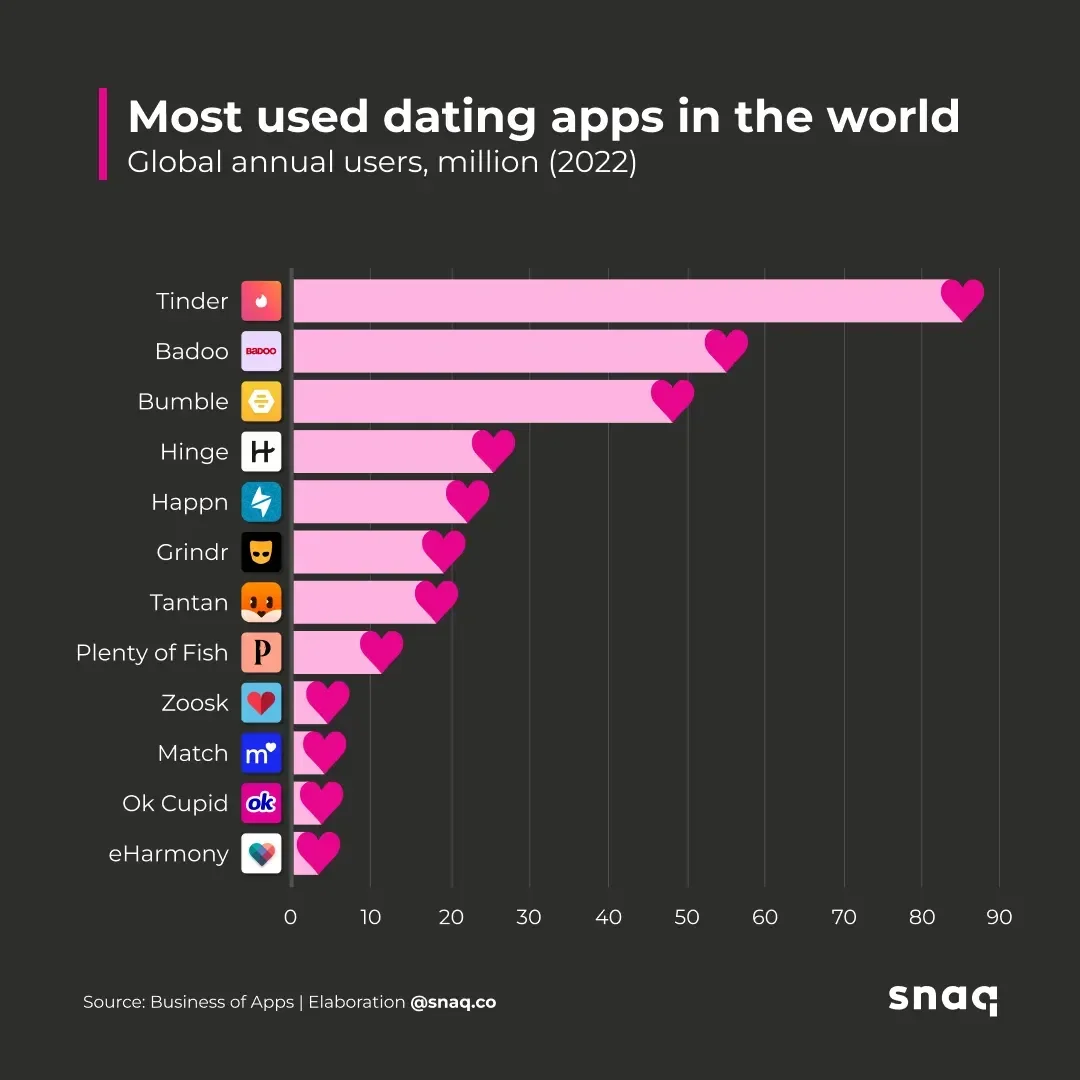

Despite concerns about gamification and disposability, dating apps have also transformed how people form relationships in positive ways. For many users, especially those in small communities, marginalized groups, or demanding academic and professional environments, dating apps provide access to social networks that would otherwise be unavailable. Platforms like Tinder, Bumble, and Badoo allow users to meet people outside their immediate social circles, potentially increasing compatibility and reducing reliance on chance encounters.

Figure 2: Tinder is the leading global dating app, closely followed by Badoo and Bumble [9].

Although dating apps may appear similar on the surface, no dating app is designed the same. Each has their own goals and ways of interaction as well as ways of solving the user’s problems. However, they all rely on similar gamified systems that shape their user behavior.

Tinder

Tinder is the prime example of making dating into a game. Its user interface reduces decision-making into two choices (swipe left or swipe right). The user can rapidly make these decisions without too much cognitive effort. Tinder transforms people into discrete, interchangeable options, reinforcing the logic of abundance.

The app relies on rewarding users with a match sporadically which creates a variable reward system similar to slot machines. The uncertainty of ‘winning’ makes it even more satisfactory to achieve a match. Furthermore, Tinder doesn’t require its users to continue conversations to remain active, which doesn’t incentivize users to form lasting connections with the people they match with.

Badoo

Badoo is one of the biggest dating platforms and also uses a swipe-based interface. The emphasis is placed more on volume and discovery by encouraging users to browse a wide variety of nearby profiles. This perpetuates a sense of constant availability and encourages the search for someone better.

Furthermore, the scale of this app increases the paradox of choice. Increased exposure should create a greater chance for better matches, but instead, the volume of other people users see can discourage commitment and create more of what Bauman described as liquid love.

Bumble

Bumble is the outlier with this group of dating apps. Bumble requires women to send the first message in heterosexual matches, which flips the traditional American social dynamic of who takes the lead in pursuing a romantic relationship.

Although Bumble also relies on the swipe-based model, it includes a time limit for each match which promotes urgency in decision making. While succeeding in promoting interaction, Bumble still prioritizes activity and retention with increased notification and reward-based matches.

What can we learn as engineers and designers from these dating apps? First, it is essential to define what problem is being solved (if you want more info on why this is important I wrote an article on it). Is the goal to retain users indefinitely, or to help them succeed and move on?

In fields like healthcare and education, success often means the user no longer needs the service—patients recover, students graduate. Dating apps face a similar ethical tension. If the goal is to foster meaningful relationships, designers must be willing to help users leave the platform. If the goal is engagement and profit, users risk becoming the product.

Empathy is a core part of the design process. People searching for love may not want to participate in systems that commodify connection. In the dating world, love should be the product—not other users. Designers must ask: what is the true end goal for the people using this technology?

Conclusion

Dating apps illustrate how design choices shape human behavior at scale. Features like swiping, notifications, and match rewards turn dating into a game-like system that encourages constant engagement and searching. While these platforms promise connection, they are optimized for activity, not resolution.

For designers and engineers, this raises an ethical challenge: what should success mean? If the goal is meaningful relationships, optimizing for time spent and user retention may conflict with user well-being. Design is never neutral—systems reflect values. Dating apps show that engineers are not just building interfaces; they are shaping how people approach love, commitment, and choice.

References

[1] Curry, David. “Dating App Revenue and Usage Statistics (2026).” Business of Apps, 7 Jan. 2026, www.businessofapps.com/data/dating-app-market/.

[2] Gorny, Liz. “Swiping, Prompts and The Ick: Has Design Changed How We Date Forever?” It’s Nice That, 3 Apr. 2023, www.itsnicethat.com/features/how-design-has-impacted-relationships-thematic-graphic-design-030423.

[3] Stampler, Laura. “Inside Tinder: Meet the Guys Who Turned Dating Into an Addiction.” Time, 6 Feb. 2014, time.com/4837/tinder-meet-the-guys-who-turned-dating-into-an-addiction/.

[4] Hobbs, Mitchell, et al. “Liquid Love? Dating Apps, Sex, Relationships and the Digital Transformation of Intimacy.” Journal of Sociology, vol. 53, no. 2, 5 Sept. 2016, pp. 271-84. SAGE Journals, doi:10.1177/1440783316662718.

[5] “You Decide.” YouTube, uploaded by Brain Games, 14 Sept. 2013, www.youtube.com/watch?v=qosYJvMZJFA.

[6] “Study: 9 Percent of Americans Are Using Dating Apps This Valentine’s Day.” Newswire, 11 Feb. 2024, www.newswire.com/news/study-9-percent-of-americans-are-using-dating-apps-this-valentine-s-day-22244002.

[7] Cicchirillo, Vincent, et al. “Quest for Connection: Motives and Gamified Approaches to Continued and Compulsive Dating App Engagement.” Atlantic Journal of Communication, 4 Mar. 2025, doi:10.1080/15456870.2025.2473451.

[8] Liu, Alina. “Why Dating Apps May Be Keeping You Single.” Psychology Today, 10 Feb. 2022, www.psychologytoday.com/gb/blog/a-therapists-education/202202/why-dating-apps-may-be-keeping-you-single.

[9] “Mapped: The Most Used Dating Apps in the World.” Voronoi, Visual Capitalist, 2024, www.voronoiapp.com/markets/Most-used-dating-apps-in-the-world-1095.

To cite this article:

Sunday, Emelia. “How Dating Apps Are Designed.” The BYU Design Review, 11 February 2026, https://www.designreview.byu.edu/collections/how-dating-apps-are-designed.