Marketing Pulls Versus Engineering Pushes

Many beginning product designers have had the experience in which they start to design a new product and begin with creating “How Might We” statements. They help us define the problem [1]. As many designers know, it is vital to define the problem and ensure that scope creep does not take place.

Most of the “How Might We” statements that are created come from feedback that is obtained from end users. For example, some “How Might We” statements might look like “How might we make this system so that it has fewer moving parts?” or “How might we use less plastic when manufacturing this part?” Sometimes, in more corporate settings, those statements come from a complaint history and from a marketing team. In some arenas, this is referred to as a “Marketing Pull.”

During my time as a design engineer, I have thought that this was the only “true” way to make sure that what I was designing was what the end user actually wanted. I wanted, with every fiber of my being, to make sure that I did not design in a bubble and try to send out a product that I thought could fix the world but no one else would want.

Recently I ran across a quote that challenged that way of thinking. My eyes were opened to a new influence for my design work. The quote has been attributed, perhaps falsely, to the great Henry Ford, the father of the automobile, and he said:

““If I would have asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses [2].””

This quote got me thinking. It’s true that customer feedback at the time would have dictated that Henry Ford should just breed stronger and faster horses since no one had even thought of the automobile and the motor engine. However, we now know what is used in regard to travel and farm work nowadays, and it does not like carrots as a snack.

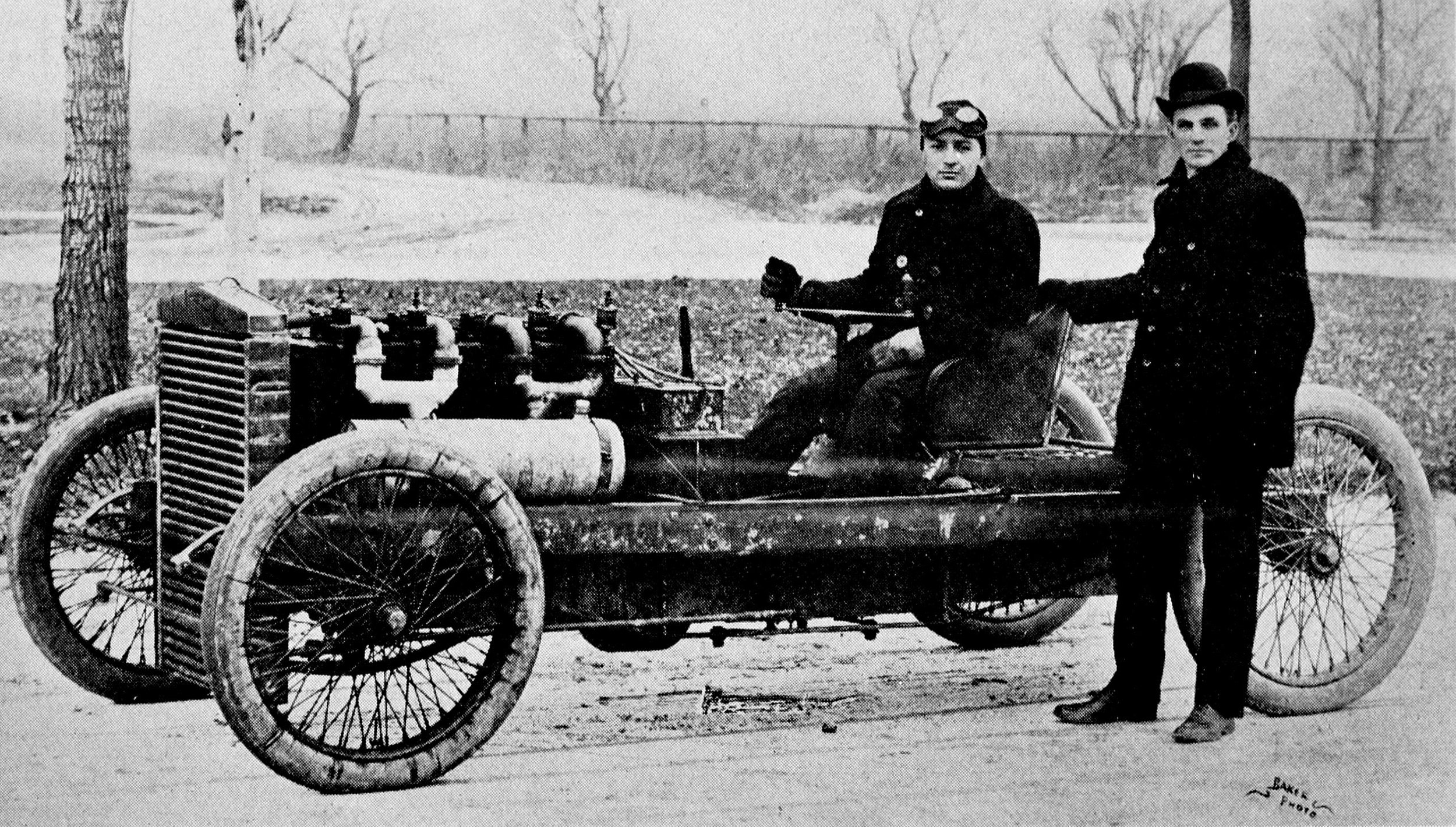

Barney Oldfield (sitting) and Henry Ford (standing).

When I asked those around me what they would term this disregard for what the end user was asking for and instead creating a new piece of technology, they termed it an “Engineering Push.” I really liked how they used the word push. It shows the dichotomy between designing based on what marketing and the end users informed the company of and what research and development had produced in terms of innovative technology.

While we as designers innovate to make this world a better place, we should not box ourselves into a corner in the name of pleasing the end user. There are times that we simply must educate the end user on what they do not know exists yet. Often, the consumer is more pleased with what they have gotten. Look at some of the big names, and some not so big, we see today: Jeff Bezos, online shopping; Mark Zuckerberg, social media and a new way to share information with friends and family; Steve Jobs, the creation of the iPod touch and iPhone; Josephine Cochran, using water pressure to clean dishes. Each of them created something new that the people:

Did not know that they wanted

Now struggle to envision a world without their innovation.

With these examples of people designing based on an “Engineering Push” rather than a “Marketing Pull” in our mind, what should we, as the designer, do when we do not feel as if we know how to identify areas in which the technology can be improved upon? A common method is to evaluate the process of how an item is used. While marketing pulls usually tend to revolve around the user’s experience, engineering pushes tend to reform the process. Think of the evolution of the calendar, to the Personal Digital Assistant, to the smartphone. Each one of those innovations created a new technology and reformed a process by making it easier to create, change and update one’s schedule.

Now one might ask, at the end of the day, “Which is more important to a designer, an engineering push, or a marketing pull?” I would respond that both are important and to implement whichever leads to greater innovation and is a better help to the human race.

References

[1] Mattson, C. (2021, September 16). Design thinking part 2: Design thinking as a step-by-step process. The BYU Design Review. Retrieved July 13, 2022, from https://www.designreview.byu.edu/collections/design-thinking-part-2-design-thinking-as-a-step-by-step-process?rq=HMW

[2] Henry Ford, innovation, and that "Faster horse" quote. Harvard Business Review. (2014, July 23). Retrieved July 13, 2022, from https://hbr.org/2011/08/henry-ford-never-said-the-fast

To cite this article:

Hollingworth, Bradley. “Marketing Pulls Versus Engineering Pushes.” The BYU Design Review, 18 Jul. 2022, https://www.designreview.byu.edu/collections/marketing-pulls-verses-engineering-pushes.