Mapping Rick Rubin's "The Creative Act" to Engineering Design

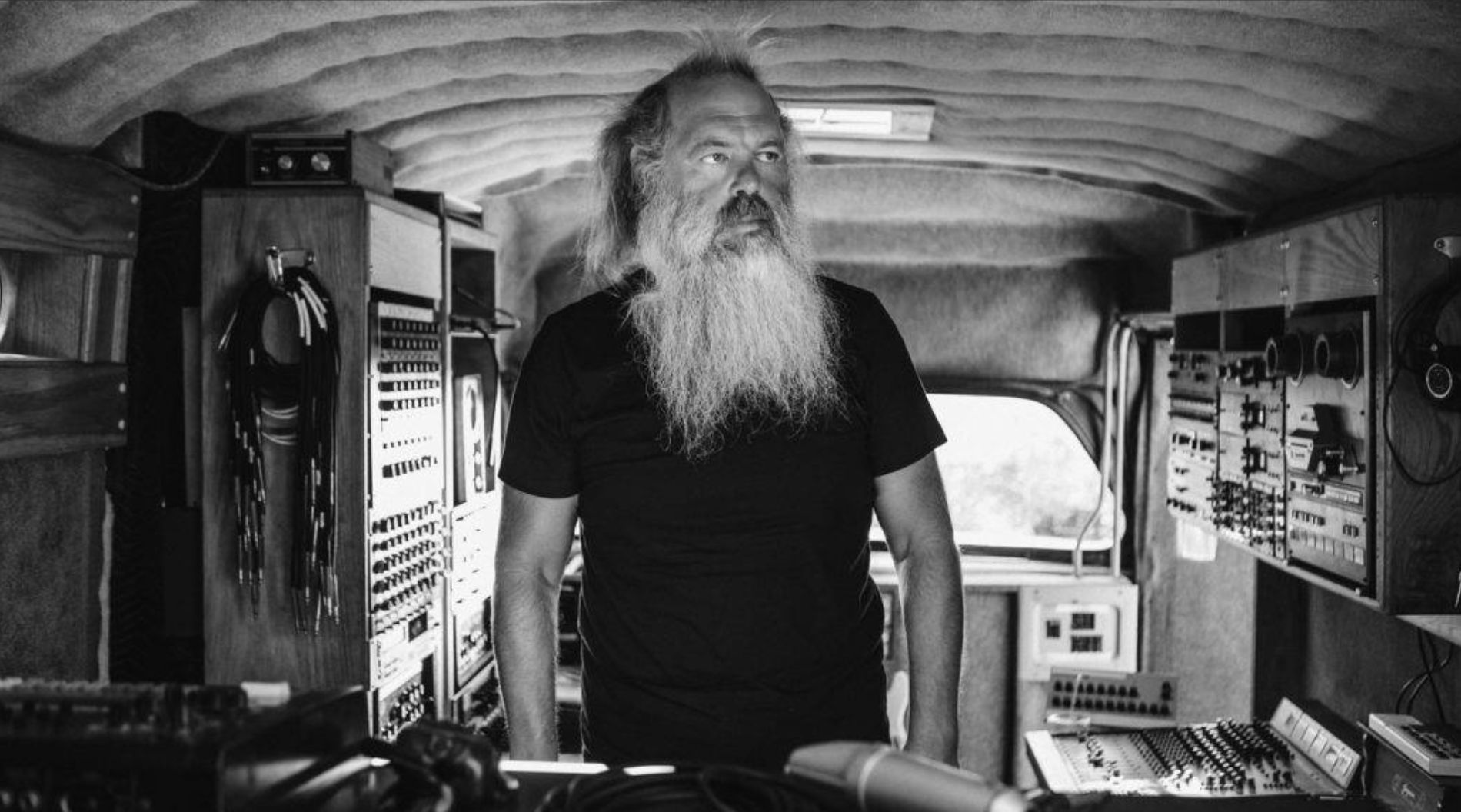

Rick Rubin is one of the most influential record producers of the modern era. His work crosses musical and cultural boundaries – from hip-hop to heavy metal, from Johnny Cash to the Red Hot Chili Peppers [1, 2]. Over a forty-year career, he has shaped the sound of popular music so profoundly that Time Magazine named him one of the world’s 100 most influential people [4]. Yet what makes Rubin remarkable is not just the range of artists he has guided, but the way he guides them. He approaches creation less as a technician and more as a monk [5] – waiting for musical truth to reveal itself rather than forcing it [4].

Rubin’s methods are famously thin – without excess. He often sits barefoot in the studio, eyes closed, listening rather than directing. He keeps no mixing console near him, takes no notes, and speaks only when he senses something essential. Those who have worked with him describe the experience as spiritual, even Zen-like – a process of clearing away noise until the truth of the work can surface [6].

Rubin’s Approach and Engineering Design

Through the proper lens, it is clear that Rubin’s approach to creativity extends to engineering design and product development. Undoubtedly this is surprising to engineers, whose practice often centers on precision, control, and calculation. But Rubin’s stillness is not the absence of rigor; it is a different kind of discipline – the discipline of attention. Just an engineer tests with data, Rubin tests with awareness. Both aim at the same outcome: clarity, coherence, and resonance.

His 2023 book, The Creative Act: A Way of Being [2], distills this approach into a philosophy of creativity rooted in mindfulness and observation. It reads more like a field guide to awareness than a manual on music production. For engineers and designers, Rubin’s insights offer an unexpected mirror: the creative process, whether in art or engineering, unfolds through stages of noticing, shaping, refining, and learning.

To hit these points home, this article maps Rubin’s core principles and philosophies to the more technically-oriented stages of product development presented in Mattson and Sorensen’s book on the topic [7].

What Rubin describes as creative being parallels the six stages of product development that guide professional design practice: Opportunity Development, Concept Development, Subsystem Engineering, System Refinement, Producibility Refinement, and Post-Release Refinement.

The Creative Act Across Six Stages of Development

Opportunity Development – Noticing What Already Exists

Rubin writes, “Awareness is the birthplace of creativity. Everything we need is already here.” At the beginning of a design process, awareness means seeing unmet needs and latent possibilities with patience and curiosity. Opportunity development starts not with ideas but with observation – the willingness to slow down, notice details, and listen to people. The designer, Rubin would say, learns to be still enough to perceive what is ready to emerge.

Concept Development – Discovering What Wants to Be

“The artist’s job,” Rubin says, “is to move toward what feels alive.” Engineers in concept development do the same. They generate, combine, and test ideas to see which ones carry life – that spark of resonance between user, technology, and context. Rubin’s reminder that “we’re not inventing, we’re discovering” fits this stage exactly. The best concepts often arise when judgment is suspended and possibility is allowed to unfold. “We are required to believe in something that doesn’t exist in order to allow it to come into being.”

Subsystem Engineering – Finding Form Through Constraint

Rubin teaches that “limitations are not obstructions to be removed; they are the path.” In engineering, this is where creative energy meets precision. Subsystem engineering demands choices – materials, geometries, processes – each bound by physics, cost, and manufacturability. Yet it is within these boundaries that imaginative designs mature. Rubin reminds us, “Rules do not limit freedom; they define it.” The engineer’s role, like the artist’s, is to shape ideas through disciplined constraint – to turn inspiration into function, and vision into form. When we work within limits with care and intention, the constraints themselves become the architecture of innovation.

System Refinement – Listening to the Whole

Rubin notes, “The work reveals itself as you go. Our task is to listen to what it needs next.” Integration and refinement are acts of listening – not to people, but to the system itself. Through testing and iteration, designers learn where the design resonates and where it conflicts. Often, progress means subtraction: removing the unnecessary until everything serves the whole. Rubin’s idea that perfection comes from simplicity echoes the words of other prominent designers including Dieter Rams [8].

Producibility Refinement – Making It Real Without Losing the Essence

“It’s not about how to make it perfect; it’s about how to make it real.” For Rubin, realization means allowing a work to take its final form within the rules of the system. Engineers face the same task when they transition from prototype to production. Manufacturing, assembly, and cost each impose their own realities. The challenge is to translate the concept faithfully – to protect the product’s purpose and feel while making it buildable, repeatable, and sustainable.

Post-Release Refinement – Beginning Again

Rubin reminds us, “Each piece of work teaches you how to make the next one.” The creative process, like the design process, is cyclical. After release comes learning. Engineers analyze failures, gather user feedback, and improve the next generation. The work is never finished; it continues to teach and the design continues to evolve. This humility – to keep listening and refining – may be Rubin’s deepest lesson of all.

Comparison Table

Table 1. Rick Rubin's Creative Principles Mapped to the Six Stages of Product Development

| Stage of Product Development | Rubin's Core Principle | Quote from The Creative Act | Design Reflection |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Opportunity Development | Awareness and attention | "Awareness is the birthplace of creativity. Everything we need is already here." | Begin with seeing, not solving. Observe people, patterns, and potential with curiosity and patience. |

| 2. Concept Development | Discovery over invention | "We're not inventing, we're discovering. The best work comes from being attuned to what wants to be." | Generate broadly, protect fragile ideas, and let promising directions surface before judging. |

| 3. Subsystem Engineering | Constraint as catalyst | "Limitations are not obstructions to be removed; they are the path." | Use engineering limits as creative boundaries. Let analysis and trade-offs give ideas structure. |

| 4. System Refinement | Listening and reduction | "The work reveals itself as you go. Our task is to listen to what it needs next." | Iterate toward coherence. Subtract what is unnecessary until function and intent align. |

| 5. Producibility Refinement | Realization through translation | "It's not about how to make it perfect; it's about how to make it real." | Design for manufacture and assembly while preserving the product's essence and integrity. |

| 6. Post-Release Refinement | Learning and humility | "Each piece of work teaches you how to make the next one." | Treat product launch as another test. Gather feedback, improve, and begin again with awareness. |

Closing Thought

Rubin argues that creativity is available to everyone – engineers included – and that it begins with how we see. He emphasizes that the creative life is a practice rather than a performance. For engineers and designers, Rubin’s lessons can carry real weight. The same stillness that allows a musician to hear a song’s hidden truth can help an engineer see a product’s hidden potential. His philosophy of attention invites engineers to think differently about design – as a state of awareness that can be practiced at any stage of a product’s development. When we design with stillness, we see more clearly. When we listen deeply, we make better decisions. And when we approach engineering as a creative act – not just a technical one – we move closer to Rubin’s vision of work that is both useful and alive.

References

[1] "Rick Rubin." Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rick_Rubin. Accessed 13 Oct. 2025.

[2] Rubin, Rick. The Creative Act: A Way of Being. Penguin Press, 2023.

[3] "The 100 Most Influential People." Time Magazine, 2007, https://content.time.com/time/specials/2007/completelist/0,29569,1595326,00.html. Accessed 13 Oct. 2025.

[4] Omodi, Senator. "The Monk of Music: How Rick Rubin Built His Legacy by Listening." Medium, 18 Apr. 2025, https://medium.com/@iomodi129/the-monk-of-music-how-rick-rubin-built-his-legacy-by-listening-19d7d16ac97c. Accessed 13 Oct. 2025.

[5] Klein, Ezra. "The Tao of Rick Rubin." The Ezra Klein Show, New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/10/opinion/ezra-klein-podcast-rick-rubin.html. Accessed 13 Oct. 2025.

[6] Schube, Will. "Marcus King Talks About Writing With Rick Rubin and 'Stripping It Down to the Copper'." GQ, https://www.gq.com/story/marcus-king-talks-about-writing-with-rick-rubin. Accessed 13 Oct. 2025.

[7] Mattson, Christopher A., and Carl D. Sorensen. Product Development: Principles and Tools for Creating Desirable and Transferable Designs. Springer Nature, 2019.

[8] Mattson, Chris. "Dieter Rams: Less but Better." The BYU Design Review, 27 May 2020, https://www.designreview.byu.edu/collections/dieter-rams-less-but-better.

To cite this article:

Mattson, Chris. “Mapping Rick Rubin's ‘The Creative Act’ to Engineering Design .” The BYU Design Review, 15 October 2025, https://www.designreview.byu.edu/collections/mapping-rick-rubins-the-creative-act-to-engineering-design.