Lessons from Leap Year

There are 365.2422 days in a “year” on earth.

You may or may not already know that it takes slightly more than the time required for 365 revolutions of our earth to get back to the same position in our orbit around the sun. But since our calendar only deals with days in whole numbers, we find ourselves a little behind our usual orbital spot on the morning of January 1st each year. In fact, as you also probably know, we “fall behind” for three years in a row before we insert a little day at the end of February and catch up or leap forward to that spot we should be at in our orbit on March 1st. These special years are called “leap years”, with February 29th called Leap Day.

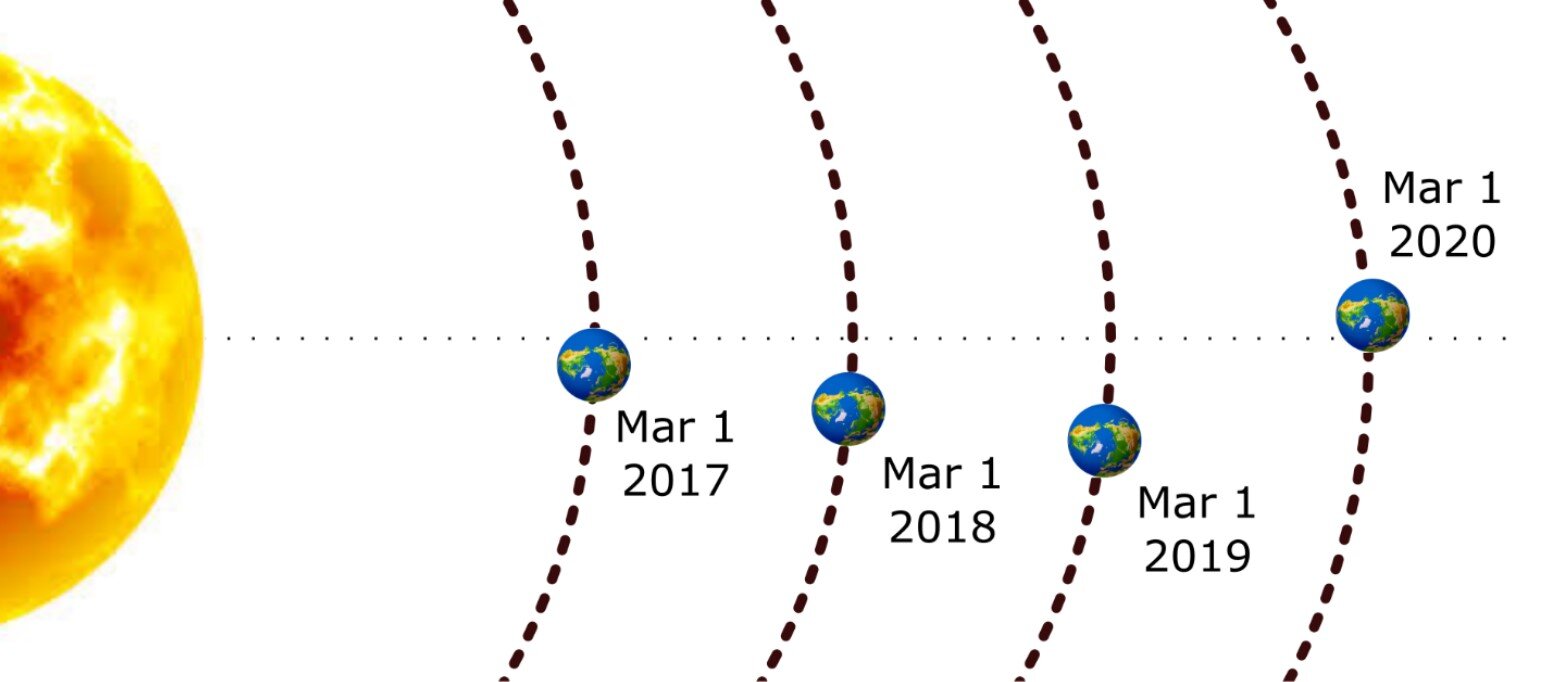

The following figure shows a very not-to-scale explanation as to why we call this phenomenon leap year (with some exaggerations). We fall behind around a quarter of a day for each orbit of the sun. During a leap year the earth, in a way, leaps forward in our orbit and returns to where we could be if everything astronomically worked out in perfect ratios of whole numbers. After the leap day of 2020, we will be back at the “right spot” on March 1 designated with the straight dashed line. (Well, close to the right spot, as we’ll discuss shortly. )

This algorithm would be perfectly fine if there were exactly 365.25 days in a year. But there isn’t. There is slightly less than 365 and a quarter days. This means after many years of the repeated pattern of three years with 365 days and then one year with 366 days, we will find ourselves ahead of our usual spot in the orbit. (See the figure above again). To bring us back to the right orbital position, designers of our calendar sometimes skip a February 29th during some of those years that could have 366 days. How often? Every 100 years. But even that’s not enough. We need to add back in a year with 366 days every once in a while because over a long time we will fall behind again (every 400 years).

All of these special refinements are necessary because the number of days in a year isn’t a whole number. In fact, scientists know the exact number more precisely than the 7 significant digits mentioned above.

So, what are the three simple rules for knowing when leap years occur?

Every year divisible by 4 perfectly is a leap year.

But every year divisible by 100 perfectly IS NOT a leap year.

But every year divisible by 400 perfectly IS a leap year.

For those readers old enough to remember, we got to use all the rules and conditions back in the year 2000, which is divisible by 4, 100 and 400. That doesn’t happen again until the year 2400. Interestingly, even the above system is not perfect. After another few thousand years, we will be a day ahead and perhaps have to skip one of those leap years to reset our calendar.

The modern Chinese society now uses the Gregorian calendar like most of the world but the ancient Chinese calendar, linked to the cycles of the moon, can sometimes require a leap month. The early Romans had something similar where they began to have a short leap month of 22 or 23 days every other year since their calendar was 355 days long. This was required to realign the time of the year with the seasons and stars. Later, Julius Cesar corrected this “frequent leap month” by making the year 365 days long and having one leap year day every four years. Finally, in 1582 Pope Gregory XIII refined this process into the rules discussed above (since one leap day every four years is too many). The world slowly converted over to the Gregorian calendar, with many countries skipping up to 13 days in order to fully adopt. For example, in North America, the month of September in 1752 was 11 days shorter and Turkey made the switch less than 100 years ago!

What’s the design lesson in all this? I see at least four.

A lot of designs aren’t perfect. Small fixes, software patches, product recalls, occasional repairs, oil changes, and sensor recalibrations are just some of the things that need to be implemented for a design to work over its full intended life-cycle. Most designers don’t think about these small things, and rightfully so. Some things are too insignificant to be dealt with right away, and those problems can sometimes be dealt with at a later date. If not, the product release date would never come. After all, perfection can be the thief of the 95% solution. If we waited for the design of a car that never breaks down, we’d still be riding horses. Despite the annoying software updates and installs we seem to be subjected to, I try to remind myself that a useful, but imperfect, system is better than a non-existing perfect one. This is true in products and it is true in people.

End users can be receptive and adaptable to anomalous conditions with the appropriate design. A lot of people look forward to February 29th. On the other hand, a lot of people can’t stand Day Light Savings (myself included!). It’s fun to celebrate that friend’s birthday or throw a leap year party with family members. It happens rarely and doesn’t impact your life too much. Yes, we all miss our turn for a birthday on Saturday at one point in our lives because of leap year, but for the most part life continues without any interruptions. But what if that leap year day was split into four 6-hours time shifts? You and I might protest on the streets if a 6-hour time shift happened happened every year (instead of the 1 day every four years). Imagine the uproar if a majority of us had to start school at night and sleep during the “day” hours, and then the shift happened again 12 months later. Many of us actually do this, at a reduced scale, of one hour every 6 months for Day-Light Savings - which I oppose vehemently. (If you’re not on my side of the fence you must not have children yet.) As a designer, dealing with the anomalous conditions of your product in the lives of your users can be vastly better with a little thought and preparation. I like how on my phone I can choose when and how to reinstall updates. On the other hand, I’ve lost precious data from an automatic computer update that forced a restart during the night while my simulations were running. In my mind, the designers of these two very different processes are venerated and despised, respectively.

A simple and memorable set of rules can be helpful. Recently, the recommendations for administering CPR were updated to make it easier for first responders to help and ultimately save lives. Short but effective protocols that can be remembered and quickly followed almost always outperform complicated checklists and messy instruction flows. Rarely do people complain about a design looking too simple or easy to interface with, but often the opposite brings about single-star reviews and poor revenue streams. The simple rules for leap years are easy to follow and remember. To give a counter example, the same alignment of our year on earth’s orbit is satisfied if we made leap day on the years that had a remainder of 3 when divided by 4 (i.e. 2003, 2007, 2011 and so on) and have the last year of every century skip leap year - rather hard to follow. The current rule set is much clearer. A good designer should look for simple and short ways to educate, inform, or instruct their users into the operation of their product. Ikea and Apple are good examples of this philosophy. Additionally, many more companies are now following this trend and that’s a good sign. You and I should follow this trend too.

People take time to adjust, accept, and adopt. As a designer, you probably want to change the world for the better. At least I hope you do. We all should. But things do take time. In the beginning, many people will not want to even hear about your big idea or world-changing design. You might have to wait until you have influence, more experience, or are in a position of leadership to fully realize your dream. But that doesn’t mean you can’t start now to make a difference or at least plant the seeds to make a bigger difference later. Start now iterating on your ideas even if they’re underdeveloped, unclear, or unrefined. If it takes a decade or even a full generation for others to recognize your genius, then get going. Something as obvious (in retrospect) as leap year took some countries hundreds of years to adopt. True, you and I might not even be around to witness the full acceptance of your ideas and designs, but the intrinsic motivation that many who come after you can benefit from your efforts should hopefully keep you going during those inevitable setbacks, delays, and obstacles.

While celebrating leap year (a more-rare occurrence than even total solar eclipses) remember that your designs often don’t have to be perfect, the end-users can deal with anomalous conditions if properly prepared, you can start now and give people time to accept your design, and always err on the side of simple layouts, instructions, and principles.

To cite this article:

Salmon, John. “Lessons from Leap Year.” The BYU Design Review, 25 Feb. 2020, https://www.designreview.byu.edu/collections/lessons-from-leap-year.