Ideation Techniques: Affinity Mapping

Engineers, scientists, and designers all gather data and then try to make sense of it later. We have equations and models to help us simulate this data. But we also have a problem – these tools were designed for numerical data, and not all data is solely quantitative.

What do we do when the data isn’t a bunch of numbers? Perhaps your data set is a notebook full of user testing you performed with a prototype, or your boss told you to dig through 532 amazon reviews to find improvements for your next product, or you just finished a fire brainstorming session with your friends and you now have 257 sticky notes with scratchy sketches and sloppily written ideas to sort through.

Have you ever found yourself in a similar bind? Affinity Mapping can help you find meaning in these kinds of situations.

The Origins of Affinity Mapping – Jiro Kawakita’s KJ method

Originally known as the KJ method, affinity mapping (also known as affinity diagramming) is an abductive reasoning process that enables people to make sense of large amounts of subjective, qualitative, or observational data. The KJ method is named after the man who created the method, Jiro Kawakita.

Jiro Kawakita was a Japanese anthropologist who struggled with this same kind of problem. He was conducting field studies in Nepal and felt like western philosophies and deductive reasoning were not equipped to analyze the observational data his field studies were producing. He formed this organizational process to make sense of his data. An engineering or design team might use affinity mapping to organize ideas from a brainstorming session, categorize types of user feedback, or to converge upon a particular idea during concept selection.

The Process

1. Gather Information and Make your Cards

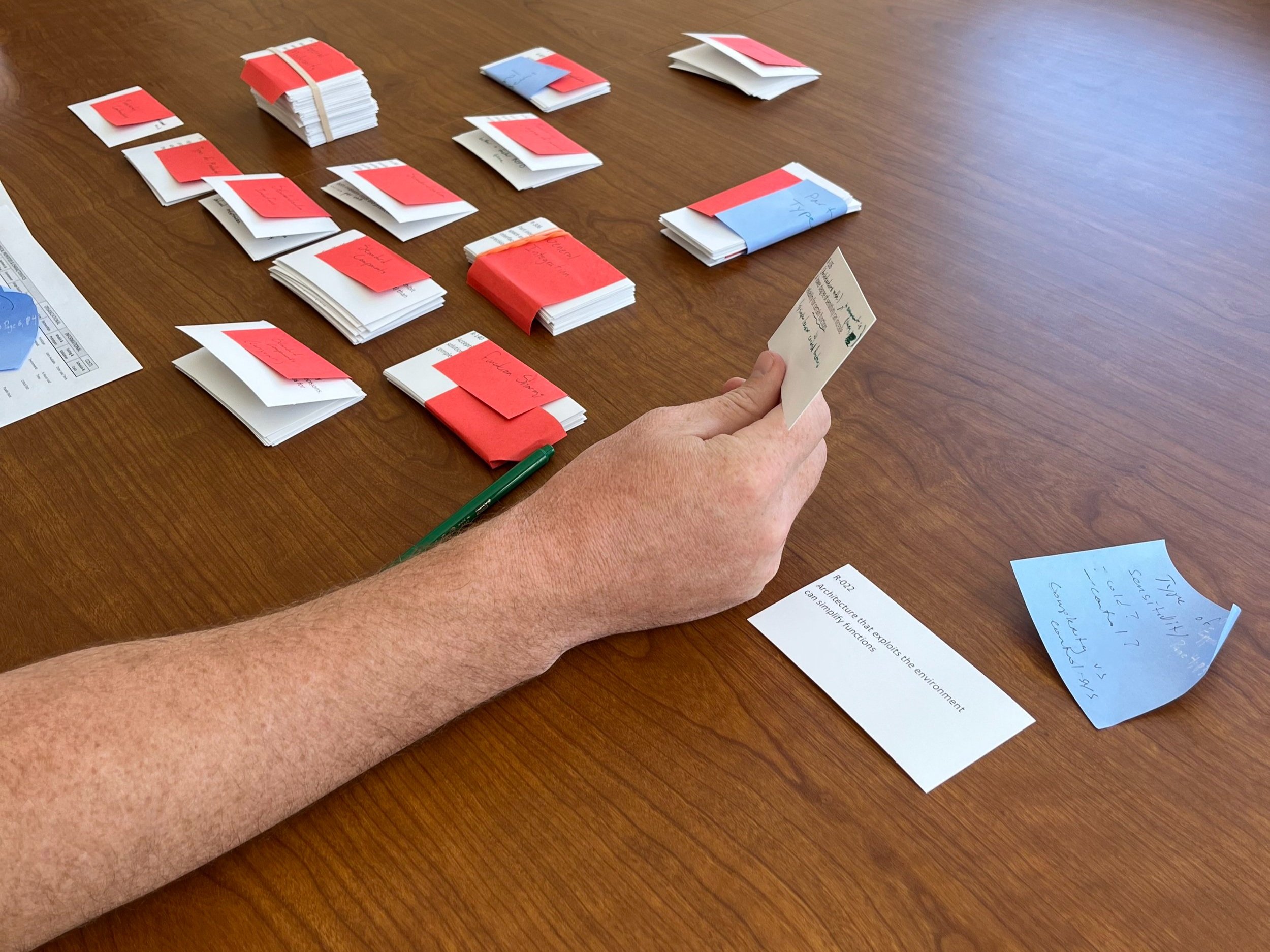

Members of BYU’s Design Exploration Research Group used affinity mapping to organize observations gathered from a literature review.

Observation based data should be gathered and written down on cards. Kawakita’s data would have come from observations he made during field studies. The examples I listed earlier, like notes from a user test, product reviews online, or ideas generated during a brainstorming session, would all be excellent candidates for observations. Continuing the user test example, every line or bullet point in your notes could become its own observation written on a card.

There’s a lot of power in having physical cards for this process. Consider using sticky notes or printing something on paper. While there is software available if you want to use virtual sticky notes, being able to see everything on a table makes it easier.

2. Randomize the Cards

Take your cards with one idea each and randomize them. If their pre-randomized order is important, assign each observation a new “random ID” that attaches it to the original idea. Randomizing your data set decouples any preconceived notions you have with the data, opening your mind to new connections and relationships.

3. Group Observations into Teams

Using your intuition and feelings, put the observations into natural groups. We’ll call these groups “teams.” Don’t worry about having a specific strategy for grouping. The strategy will naturally emerge as you use your abductive reasoning skills and sort through the data

During this step, it’s normal for “lone wolves” to appear in your data – observations that don’t seem to fit with any other team. That’s ok. Don’t force lone wolves into piles they don’t belong to; just let them be for now.

4. Assign titles to teams

Every team (pile of cards) got a title, written on a sticky note.

Give each team from step 3 a title. You can also think of these titles as labels. Lone Wolves do not need a title assigned, they will be left alone and brought into the next step.

5. Repeat step 3 using the titles and lone wolf cards.

Group the titles into new teams. Repeat this step as many times as necessary until it doesn’t make sense to make any new groups.

6. Analyze the Relationships

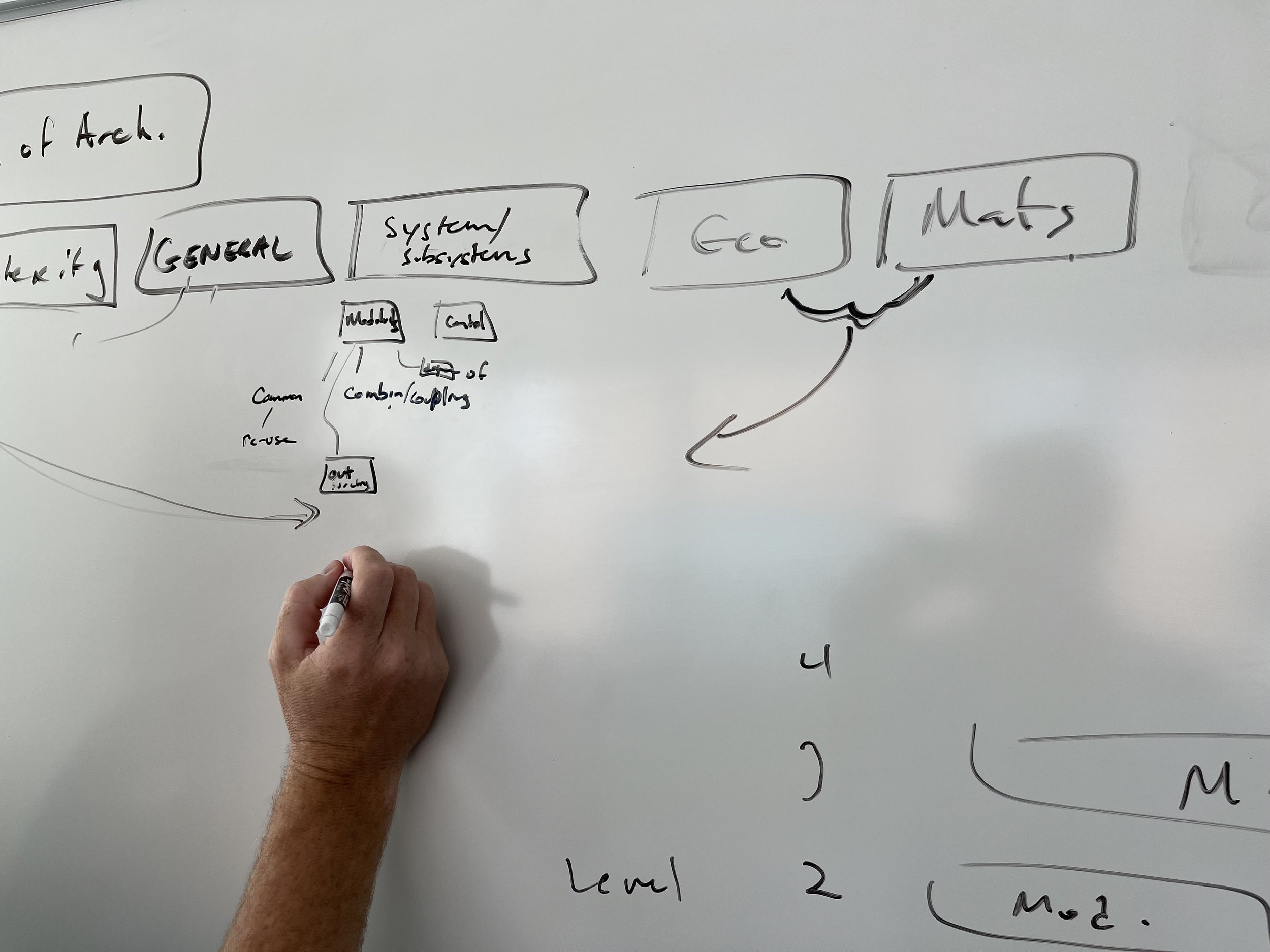

We used the groupings created in our affinity map to create a flow chart. If you look closely you can see my reflection on the whiteboard as I take a picture, haha!

This process of organizing data will draw patterns and relationships to the surface. What trends, patterns or themes do you see amongst your teams and groups? The relationships and patterns you identify in this step will point you towards innovative solutions.

For example, suppose you did this activity after brainstorming ideas for a new project. You may notice that your ideas fall into three or four main ideas, and moving forward your team could decide to prototype one idea from each category for further development.

Using Affinity Mapping in Design

For the most part, educational institutions teach students how to solve well defined problems, like the ones you’d see in a textbook. However, design challenges are hardly – if ever – defined. Design problems are open ended, ambiguous, and often include challenging constraints with no clean answer.

Affinity Mapping is a powerful approach to design. When confronted with t a problem or opportunity that has resisted a solution, you can write down everything you know and have observed about the problem, and use the KJ method to find overarching themes that connect main ideas. Ultimately, the KJ method is about discovering something new. Keep it in your back pocket as an ideation tool, and it will be there for a variety of design needs.

Sources:

To continue learning about the KJ method, see The KJ Method: A technique for Analyzing Data Derived from Japanese Ethnology by Raymond Scupin.

Scupin, Raymond. “The KJ Method: A Technique for Analyzing Data Derived from Japanese Ethnology.” Human Organization, vol. 56, no. 2, 1997, pp. 233–237., https://doi.org/10.17730/humo.56.2.x335923511444655.

To cite this article:

McKinnon, Samuel. “Ideation Techniques: Affinity Mapping.” The BYU Design Review, 19 Sep. 2022, https://www.designreview.byu.edu/collections/ideation-techniques-affinity-mapping.